But the cattle barons of Brazil faced an additional enemy in addition to wild natives, rustlers and disease: Jaguars, or tigres, as the Brazilians called them. An average tigre easily outweighed even the largest of pumas, regularly reaching three hundred pounds of rippling muscle, and some reaching four hundred pounds, landing the cats in the same realm as African lions. Although they never achieved the man-eater status of lions, Indian tigers or leopards of the Old World, for reasons I can't fathom, they were never the less impressive predators that could disembowel any man or dog that sought their dappled pelts, or crunch the vertebrae of the largest steer they crossed paths with.

And unlike the grassy veldts of Africa where one might hope to hit a lion at a hundred yards or more should one spot a patch of tawny hide, tigres concealed themselves in the green mazes and morasses of the jungles and swamps, where they might hide within mere feet of a hunter without being spotted.

Its not difficult to see that hunting a tigre, or jaguar, even under good circumstances with a good rifle would prove difficult.

And it is here that we come to the subject of this article, an exceptionally rare man who not only made a living out of hunting the deadly tigre on its own terms, but did so with naught but a handful of good dogs and a spear!

Joaquim Guato was a pure-blooded Indian of the Amazonian interior, predictably of the Guato Indians. All we know comes from who would become his student, a Lithuanian emigrant who traveled to the steaming jungles in search of diamonds and more importantly adventure, a gentleman by the name of Sasha Siemel, who has thankfully listed much of his activities in books that survive to this day. However, Senor Siemel is not the subject of this article, but his esteemed teacher.

Joaquim was not just a casual hunter of tigres, but pursued them with such deft skill and precision as to defy the belief of ignorant civilized man. He was of an extraordinarily rare breed of men known in the jungles as a "tigrero", a man who specialized in hunting the beasts with only a zagaya, a six foot long spear with a broad head of pounded iron and cross bar to prevent the feline from wiggling its way down the shaft and to the hapless wielder, not terribly unlike a boar spear.

Sasha had heard of the mysterious hunter from a number of people, and found himself hopelessly fixated with seeing if the tales were true. After a great deal of travel and searching the European found his hut, and with grand anticipation called upon the occupant. Joaquim was not what he was expecting. A tiny man of indeterminate age, likely sixty years or older, and tottering from enough booze to land him on the verge of alcohol poisoning. The tigrero was distraught at the audacity that a nearby Dom had offered him simple money in exchange for his prized hunting dog, Dragao.

That Joaquim loved his ruddy pooch was evident from his unmasked affection, going so far to kiss the mongrel in front of his guests. Senhor Siemel at this point was unsure what to make of the little man, but accepted an offer to join him on a hunt the next day. Siemel doubted the little man could sober up in a week, let alone under 24 hours. However it became evident that Joaquim had a liver of cast iron, for the next morning he was as fresh as could be, ready with his proud spear and dog. His method at first seemed simple: Go to where cats were likely to be about, let his dog Dragao pick up the trail and lead them to the puma or tigre, and spear it.

It is worth noting that Siemel, while not tall, was extremely strong and physically fit. Although under six feet and had the appearance of a professor, he became well known for his feats of strength, toppling two men of immense physical stature and power in boxing and wrestling, nor was he a stranger to long walks and enduring the elements. But as they set off through the early morning jungle he found himself lagging embarrassingly behind as the little Indian set a straining pace, seeming to glide through the foliage as if it were mere fog, appearing to be immune to fatigue whilst the European panted for breath and was basted in sweat.

Siemel was understandably astounded by the little man's endurance and frequently lost sight of him. For more than an hour the three followed the trail of a wily mountain lion until at last they found it at bay in a tree, Dragao snarling and glancing impatiently at his human companions who seemed to delay. Siemel wished to have a picture, but as he unfastened his camera he was stricken with the change that seized Joaquim: Although relaxed he was alert and prepared, soaking up his every surrounding with wilderness-carved instinct, but focused absolutely on the cat in the tree. It is difficult to convey they all-encompassing sense of comprehension and concentration the little Indian exhibited, sensing everything around him and yet not relaxing his focus for a moment. For as Siemel would learn, to be distracted for even the shortest time when spear hunting the great cats would spell death.

After securing a picture Joaquim gestured for him to shoot the puma, and as he aimed his Winchester the cat leapt from the tree. In a flash three figures moved: The cat, Dragao jumping for its throat, and Joaquim lunging with his spear at the cat. All three met at the same time. The tragic result was poor Dragao being mortally wounded even as the cat was slain. Although the Guato offered no tears or words, the expression on his face as he embraced his dying companion gave voice to his anguish greater than anything else ever could.

One might suppose that this would mark the end of his hunting career, for hunters and their canine companions are truly inseparable, and often hunting loses its charm after one has passed. The sting of grief is invariably cruel. But to Siemel's surprise Joaquim showed up the next morning with two other dogs. Although neither was an equal to Dragao, for there could only ever be one of his caliber, both new dogs were exceptional hunters. Siemel was touched by the old man's generosity, and found he had made a positive impression on him. What money could not buy, his efforts and friendship had earned, and gained his own hunting companion named Valente.

Months later they once more set out on the trail, this time bound for a tigre. Honed by countless hours hunting Joaquim dazzled the experienced Siemel with his unerring knack for finding the correct trail out of the confusing morass of leaves and mud, able to read sign as if it were spelled in plain lettering, what sort of cat it was that he was following, how long ago it had passed, what mood it was in, and almost anything else he could wish to know. So sure was his jungle sense that he seemed absolutely at home in the green nightmare. The dogs were equally excited as their masters, taut muscles quivering with anticipation.

After a chase, listening to the dogs bark and howl in the distance, the two broke upon them, the quartet of dogs growling at a copse of palms, the tigre unseen, hidden like a viper amongst a bed of dried leaves. Joaquim boldly approached, the tigre growling angrily, swiping at one daring dog and then another as they darted in with chastising snaps and barks.

It was in this arena of nature that Siemel finally saw the tigrero truly at work. The little man held his spear level with the ground, held firmly in his iron-thewed hands, eyes locked on the gold and onyx dappled cat which glared at him from the shade of the foliage, watching, waiting. It was here that the true game started, for one does not throw a zagaya at a tigre, nor does one simply prod him and hope that he conveniently bleeds to death. Joaquim had learned that one must goad a tigre into charging, and it is at that moment that a tigrero must read the cat's body language perfectly to anticipate what he will do in the fraction of a second before he makes contact. Will he rush and come in low, sweeping up at the legs? Or will he leap into the air and pile onto the hunter, rending and tearing with teeth and claws? The tigrero must understand which will come and then deliver the spear thrust. Misjudging the movements would swiftly result in a singularly messy death, looking not unlike a meat-stuffed pinata torn apart by half-starved pit bulls.

As the Indian settled into his stance, spear tucked firmly at his hip where he could throw his full weight into the thrust, he kicked a clod of earth into the tigre's face! Although animals rarely understand insult as we humans do, the tigre understood this one all too clearly. No longer did it heed the snapping dogs. It was out for the blood of this human who had dared antagonize it. It snarled and shook itself, working into a rage, until it was again taunted by a swift prick of the spear. A second prod and the cat moved, three hundred pounds of angry feline muscle launching at a man well under six feet and less than half of its weight, armed only with a spear.

Suddenly the iron head was buried in the cat's neck, the animal roaring and flailing almost in the air, tearing at the little man. It was a fantastic tangle of golden limbs flailing wildly in an attempt to rend the Indian to ribbons of gore, and yet impossibly Joaquim held the massive cat at bay, able to keep it just barely out of reach although it looked as if it were on top of him. Somehow he held back the terrific weight and fury of the animal until it yielded to his blade, attempting to free itself from its edge. The moment it gave ground he withdrew the spear and drove it home again, a mere flash of movement, this time burying the blade in its chest. In a moment the fortunes had changed, and before Siemel understood what was happening the cat was on its back, pinned to the ground, holding it there until at last it expired.

Senhor Siemel stood aghast, hardly able to credit his senses. Joaquim only grinned, undoubtedly pleased with himself and for once having someone around to witness his work. It had been a battle purely between man and animal and won with pure skill, a mastery of self, weapon and understanding of his quarry. The tigrero understood his prey so completely that he could understand them as a person understands the expressions and language of his best friend. Rather than being repulsed by this magnificent display of primal combat, Siemel was hopelessly hooked. Joaquim seemed to understand the European's sensations, for he grinned knowingly the rest of the day. Without even being asked Joaquim then sought to train his young friend.

Although the differences between the two in blood and culture were as wide as the ocean that separated their homelands, they were linked by the undying love for wild places and deeds that burns in the breasts of all adventurers. Without prompting Joaquim taught young Siemel in all he knew. Why he did this even Siemel didn't know. Perhaps he wanted to be remembered. Perhaps the tigrero knew that his breed was a rare one and wished to pass his skills onto another, for he lived apart from his tribe and had no children or other friends to inherit his knowledge. Then again, maybe he simply knew his friend wished to become a tigrero also and wished to make him happy. Who can truly know? Whatever his intentions, he succeeded beyond his greatest expectations, for in time Siemal would become a tigrero all his own and immortalize their deeds in books that would captivate the men and women of the civilized world for decades.

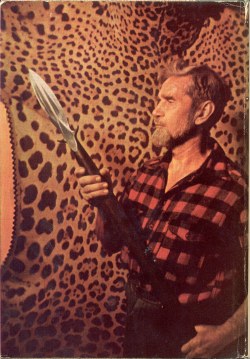

|

| Sasha Siemel and his zagaya |

If the first true tigre hunt had not been enough to convince Siemel of Joaquim's prowess, the months of practice together would remove whatever infinitely small shreds of doubt remained. Time and again Joaquim was summoned by the various Doms who held thousands of cattle under their sway. Tigres would prey on their herds, both large and small, and when their daring vaqueros proved incapable of handling the wily beasts, or if one developed a terrifying taste for human flesh, the little tigrero answered the call, slaying tigre and puma alike with his furry companions and his shining zagaya.

Sadly, like all good things, Joaquim's legendary trail came to an end. Siemel, having been gone on his own business for a period of years, returned to the tigrero's haunts and came upon a rotten canoe and a skeleton with a broken spear nearby. With a nauseating realization he found the body of his friend and mentor. The scene was easy enough to read. The hunter had been in pursuit of a three toed tigre

that had been preying on a ranchero's herd, following it over the river, and as he had entered the shallows and began pulling his canoe in by hand the cat had charged him. Unable to resist the charge it had slain him and left his bones to molder on the river's edge.

It was only some small consolation that Siemel would beat his friend's slayer, for some years later he answered a similar call and killed a jaguar with three toes.

While Joaquim's death was unspeakably tragic to all lovers of brave men, he thankfully found lasting memory in the yellowing pages of books written by his friend, even now found on used book websites and aging on the shelves of used book stores. Had it not been for the writings of Senhor Siemel, we may have been denied the priceless knowledge of this elite class of hunters, those who willingly and joyously hunted and fought the dreaded jaguars upon their own terms in the dripping jungles of the Amazon. And while it pains me to say that there is no known photo of Joaquim Guato, we have his memory. His love for his friends, his dogs and to his prey, the tigre, permeated his every action when on the trail, and it is perhaps some small consolation that he died in pursuit of the great cats that he so dearly loved to hunt.

Although it is almost assured that there are no more tigreros today, stalking the the great dappled cats through the tributaries and shadowy palms with spear in hand and dogs at their heels, we may hold the small hope that one or two still survive. But if not, they will always live in the memory of those who burn at the thought of treading the wild lands, and so long as these brave men are remembered, they will never truly die.

Cool story!

ReplyDeleteThanks! I'm glad you enjoyed it. :)

DeleteFeel free to spread it to others if you think they'll be interested.