Here I'm going to cover some of the most unique guns ever produced by the eccentric brains of the American inventors.

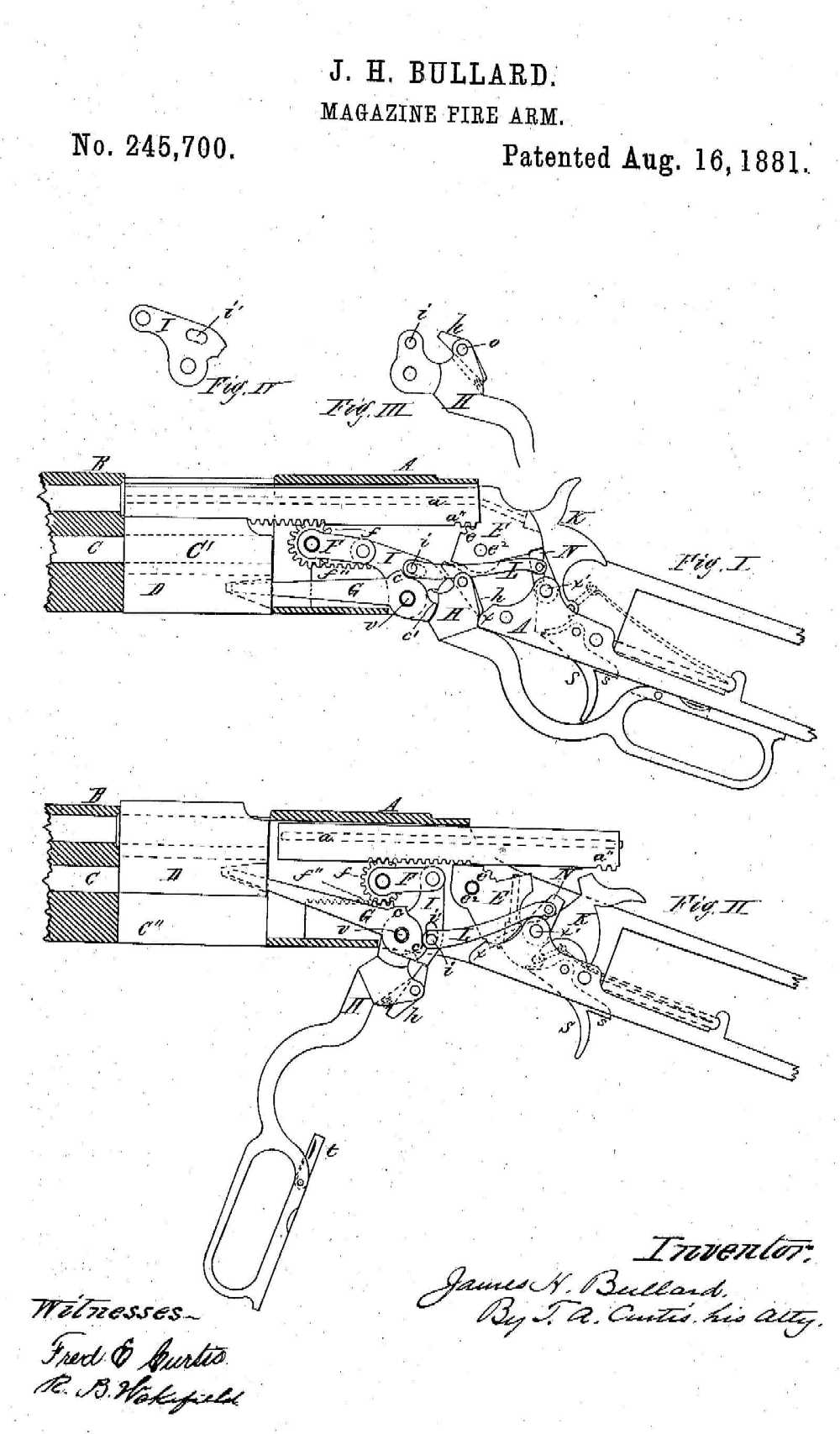

At first glance the Bullard repeating rifle doesn't seem that unusual. Not to be confused with the Ballard rifle company, the Bullard rifle company produced a series of single shots and one of the most unique repeaters ever designed. Unlike the Winchester 1873 cousin which operated on the toggle-link action, the Bullard used a rack and pinion design which was infinitely smoother and very advanced for the time. According to many owners it is one of the fastest and smoothest actions out there, and perhaps the smoothest of all lever actions. It was produced in both a frame for pistol cartridges and full sized rifle cartridges, both being of very high quality. The design was also wonderfully strong for its time, and wouldn't be surpassed until the invention of the 1886 by Browning. Another feature that makes this rifle completely unique among leverguns is that it is loaded through a loading gate on the bottom of the receiver, much like modern day shotguns. All Winchesters and Marlins are fed through a loading gate on the side of the receiver.

If one takes a look at the Bullards assembled by collectors you'll quickly notice that no are exactly alike. Each has some variation that makes it different from its brothers. A different barrel, different magazine tube, lengths, stocks, sights, all vary slightly. This indicates that these were produced as high quality custom guns for highly discerning customers. While an admirable and certainly appreciated business model, it may have helped lead to its downfall, as the high prices would have put it beyond the means of most frontiersmen.

|

| The inner workings of the Bullard |

Although its chamberings were uncommon and made little logistic sense, they were by no means weak. The 50-115-300 would have been one of the largest cartridges ever able to be stuffed into a repeater, putting even the 1876 Centennial to shame. A fifty caliber three hundred grain bullet pushed by one hundred and fifteen grains of black powder would have been capable of slaying anything on the continent. It would have been able to take down the largest brown bear, moose or bison with ample authority. It's a testament to the versatility of the design that it was able to handle such long, fat cartridges while still being so compact and handy.

Perhaps the most important factor in the fall of the company was the designer himself, James Bullard. He appeared to be an impulsive, artistic type in that he would focus on one project obsessively for several years and then move onto something completely different. His firearm designs were nothing short of brilliant, and had he stayed on with the company he developed and continued making designs the company may very well have been one of the major competitors to Winchester and Marlin. But in just a few years he abandoned the company and began working on a steam powered car, among other things. He was extremely prolific in his designing, but never stuck with one thing.

Overall the Bullard was a weapon ahead of its time. It was elegant, powerful, and one of the most gorgeous rifles produced during the era.

One would think that with the introduction of guns like the Spencer repeater or the Henry that the US military would be licking their chops. On the contrary, the head honchos showed suspicion and fear towards the fast firing weapons. They worried that soldiers would waste ammunition uselessly in rapid fire. Seven or sixteen shots available at the same time? Heaven forbid! I can only imagine these gentlemen suffering multiple simultaneous heart attacks when in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War a most ambitious inventor presented them with the Meigs rifle in 1866 which somehow boasted a fifty round tube magazine!

|

| The darned Western gun they load on Sunday and shoot all month! |

The generals of the time recoiled in horror at the idea of men armed with these, which would have put even the impressive Gatling to shame. Unlike the Gatling, the Meigs wouldn't have required a crew and extra gear to set up the weapon. But the idea of spray and pray apparently haunted their dreams, and the Meigs swiftly fell into obscurity. Only three were ever made which now reside in museums. Although it never saw the face of war it is an extraordinarily potent and fascinating piece of engineering, certainly not something one would have expected during the time it was made.

Although only in prototypes, they supposedly discharged 38,000 rounds for tests without malfunction. If so, then this was a remarkably reliable design that would have been a terror to face down at close range.

The Burgess shotgun, developed much later in the late 1800's, is one of the most fascinating and innovative shotgun designs ever made. Aside from the 1887 Winchester lever action shotgun, the pump actions reigned supreme in the hands of law enforcement and hunters in the 1890's. Then the Burgess arrived. At first glance it appears to be nothing unusual, with perhaps a slightly stubby frame and an odd grip. But these details are deceptive, for the Burgess is perhaps the fastest shooting shotgun besides the semi and full autos. Like the Meigs it used a slide action in the grip. When rolling with the recoil one naturally pulled the slide back, and once they were on target again slid the action up and were ready for a follow up shot. An experienced shooter could unleash five or six rounds of twelve gauge fury in the time it took for his hat to fall to the ground.

The designer, Andrew Burgess, was, like many other inventors on this listing, a prolific inventor. His method of making a sale with this gun however was certainly unorthodox. His salesman, Charlie Dammon, did an exhibition for a notable New York Police big wig who boasted a pair of glasses and an unmistakable walrus mustache. Haven't guessed who it is yet? Well, it was Teddy Roosevelt, one of the overall most hard core and awesome gentlemen to have ever set foot on this dirt ball. Now, most salesmen would have shown some schematics or perhaps shown his new fancy gun in a well-manicured case. This gent went a little further than that. While talking with one of the coolest men ever he pulled the weapon free from under his coat and rattled off an entire magazine of blanks. Somehow avoiding getting perforated for his shocking enthusiasm, he was instead rewarded with a bulk purchase. Teddy loved his guns and was thoroughly impressed with the capabilities of this shotgun.

But what made this weapon even stranger was that it could be folded in half, like something out of a cartoon. Even coming with a special holster, a New York officer could walk around with a full length twelve gauge riot gun under his coat and have it ready to go in no time at all. The images below, borrowed from Forgotten Weapons, show just how elegant and compact this design is.

Sadly it didn't get as much traction as its competition, but it made a distinct imprint on history and will never be completely forgotten.

Yet another queer repeater that will certainly leave a few people scratching their heads is the Evans repeater.

Developed in Maine in 1873, the same year as The Gun That Won The WEst, by a dentist by the name of Warren Evans and his brother, they, like so many other weapon designers of the time, sought the coveted military contract. And like so many others, didn't get it and switched to giving it to sportsmen and frontiersmen. Like the odd Meigs it had a hollow tube magazine sandwiched between two pieces of wood for the stock. With a barber-pole screw mechanism the lever would twist the cartridges up and into the receiver. Depending on the model, it could hold between 24 or 36 rounds, an astonishing capacity for the time, surpassed only by the Meigs. Firing stumpy .44 Evans rounds it was a decent short range fighting gun.

Around 15,000 were produced in different models, which wasn't a bad number at all at the time, but not enough to keep it afloat.

|

| An Apache with an Evans. Note the decorative brass tacks driven into the fore-stock, a common feature among guns owned by Native Americans of the time. |

Although not one of the strangest guns, the Merwin Hulbert revolvers were innovative but were also some of the most finely crafted and fitted guns of the entire 19th century.

Unlike its contemporaries, the Merwin Hulbert didn't have an ejection system like the brake open or SAA models. Intead the barrel was twisted to the side and pulled forward along with the cylinder, popping all of the spent cases free. It was a very swift way to get rid of shells, although after unloading them with the rapid double action it might have been a royal pain to grab that barrel for unloading.

|

| Mechanism for unloading |

What truly sets them apart though wasn't just the design, but the almost unmatched quality. The machining and metal fitting were extraordinarily precise. The metal fitting was so close in fact that when trying to unload a vacuum was formed and would pull the gun part way closed by itself! I've never heard of this happening with any other gun. The Merwin Hulbert company it seems wanted to not just produce pretty guns, but some of the best working-man guns out there. Most were shorter barreled .38 and .32 caliber pocket guns, meant more for being in the pockets of city folk rather than trading fire on the prairie. Some models even had a hammer spur that folded forward to avoid getting caught on clothing when being drawn. Mighty clever!

A fair number of these were produced and made a decent dent in the market considering their competition with companies such as Smith and Wesson, Colt, Remington and others, but never earned the same respect or love.

I hope to find more such oddballs and bring them to your attention. The Europeans especially came up with some queer designs during this period which differed drastically in concept and design, illustrating the different thinking and priorities from their Western neighbors.

No comments:

Post a Comment